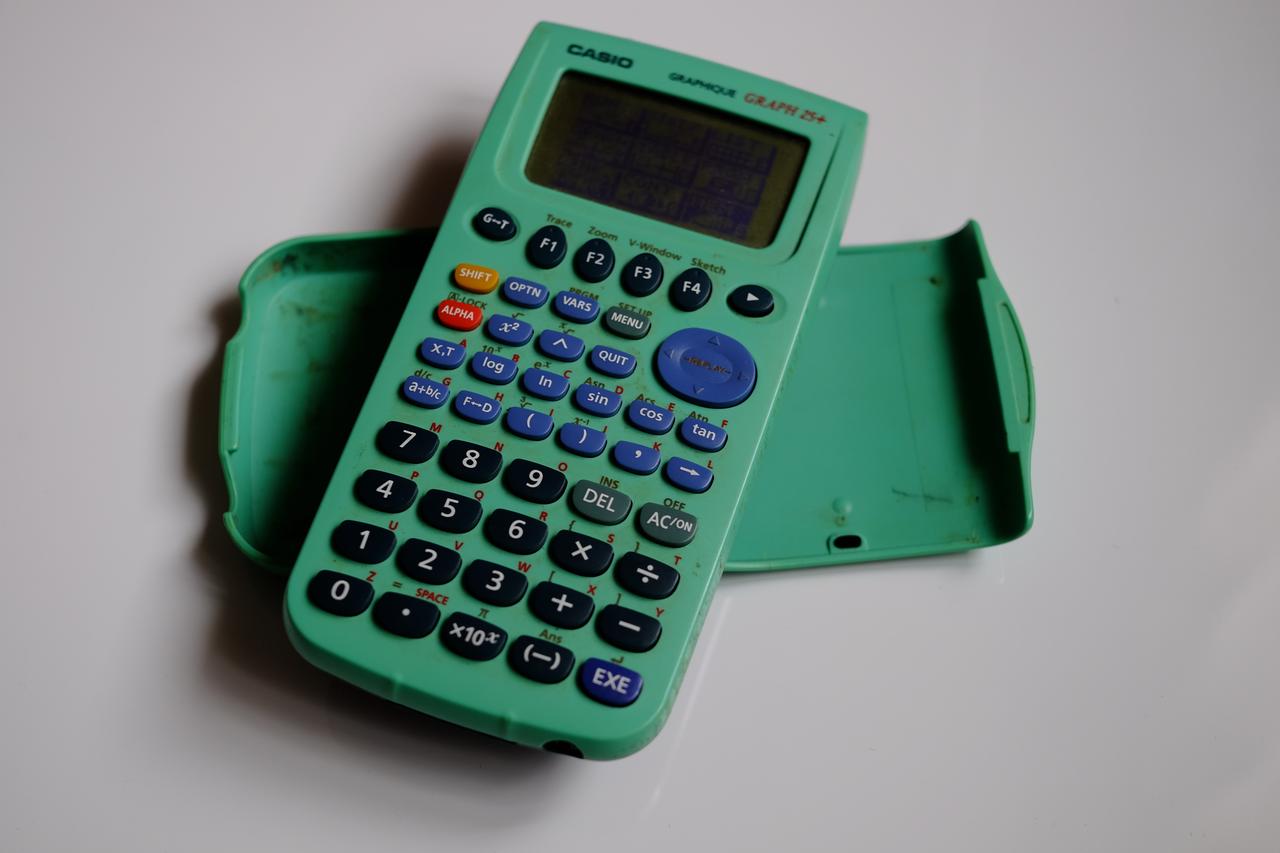

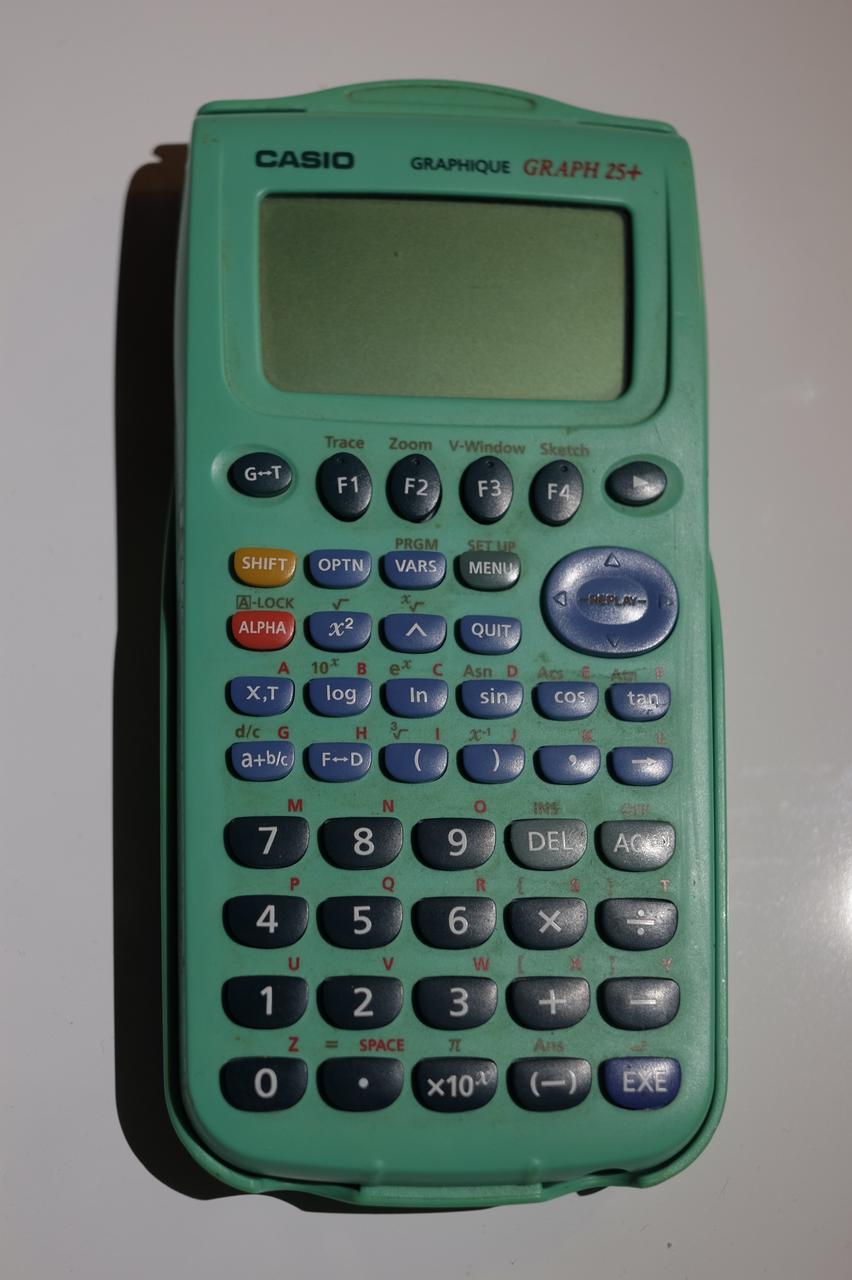

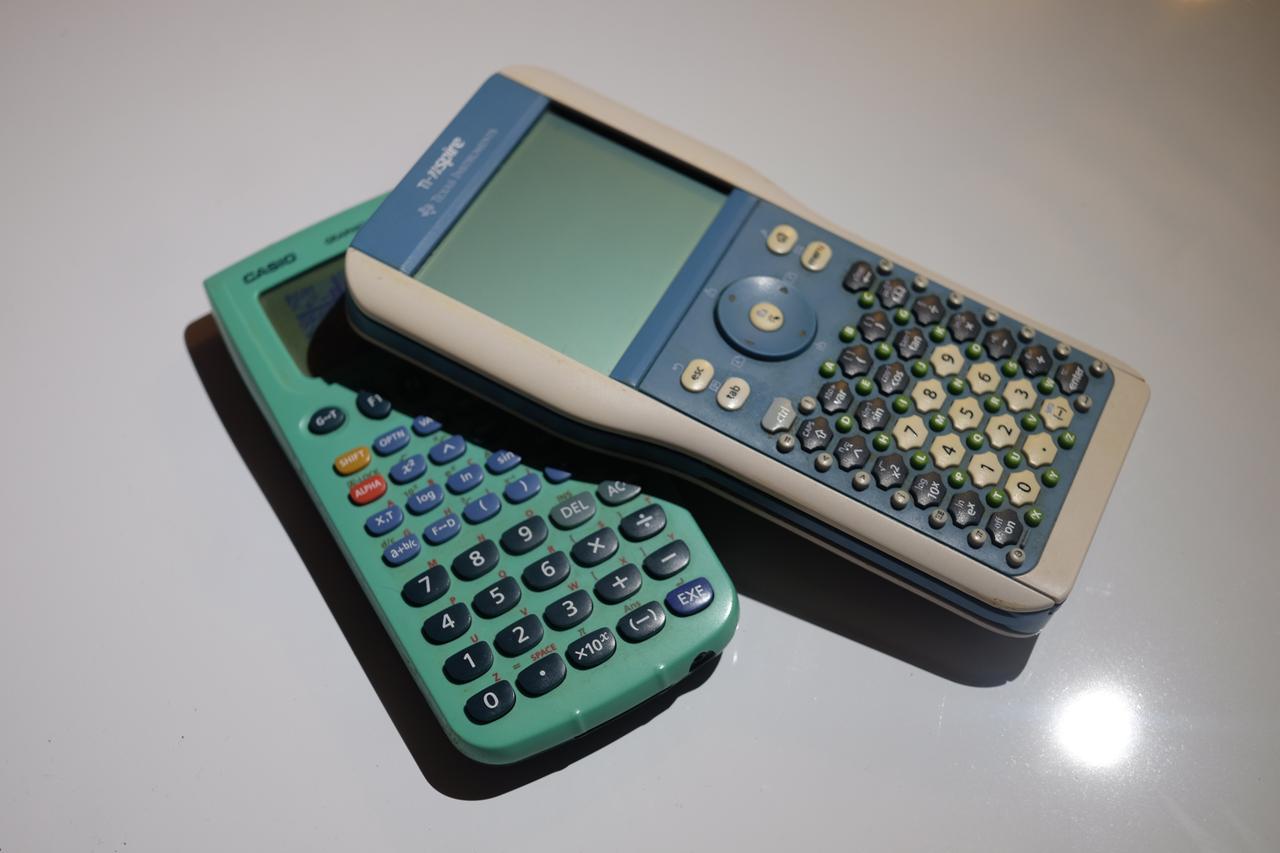

Young people today grow up surrounded by computers. Children are given smartphones and tablets pretty much from birth, and in the rare case they are not, their primary school will make sure to supply them a cheap laptop as soon as possible. Whether that abundance is an unqualified good or not is a question I’ll happily leave to the reader. More than 15 years ago, though, my own first "computer" looked very different. While my classmates already had Nintendo DS consoles (the luckier ones with the upgraded Lite version, and I was extremely jealous) and early smart-ish phones, my pride and joy was a Casio graphing calculator, more precisely a Casio Graph 25+.

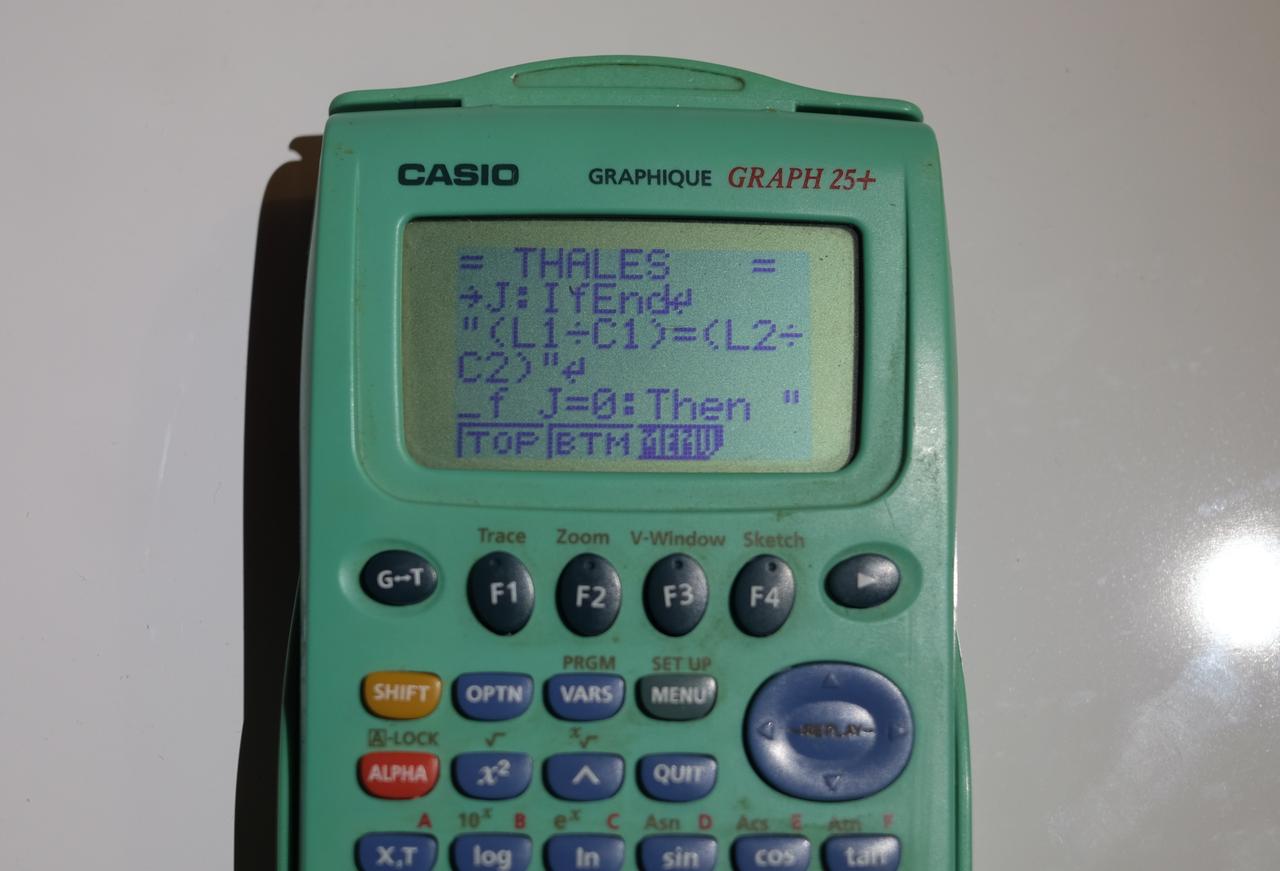

I recently stumbled upon it again while sorting through old boxes at home. Out of curiosity, I put in a fresh set of batteries. It surprisingly still worked, but even more surprising to me is that its memory was still intact. So I figured I'd take a look. If not very insightful, it might be amusing to revisit what a seventh-grade kid, with no programming knowledge but quite a lot of free time during recess, had managed to come up with.

1. How It Became Mine

This part is a bit of personal backstory. I enjoy reminiscing, but feel free to skip ahead if you’re here for the technical bits.

Before the Graph 25+, I used a more modest machine: a Casio College fx-92. It did everything I needed to follow maths lessons throughout my late elementary and early junior high years. But this state of affairs changed when my older sister started high school.

Even though she was going for the literrary program, she was told she needed a graphing calculator. Not convinced, our parents reluctantly bought her the cheapest one they could find: the humble Casio Graph 25+. An she hated it. The menu system felt unintuitive to her, there was no natural fraction notation, and she never had any use for the graphing features. Maths in general was never really her thing. So we struck a deal: she got my fx-92, which she preferred anyway, and I inherited the thick green slab.

My access to the internet was extremely limited at the time. At home, it was strictly reserved for homework, under adult supervision. So my only real resource was the user manual. It is 236 pages long, and printed in a comically small format (A6, I think). I unfortunately must have thrown it away at some point as I never found it again, but you can still find it online if you look well enough. Most of it is insanely dry as you'd expect, but the chapter on programming did catch my eye.

I was never the popular kid on the playground. During recess, while others played, I usually sat in the same quiet corner, calculator in hand, tinkering and trying things I barely understood.

2.Programming Like It's the 80's - A Primer on Casio BASIC

The Graph 25+ (known as the fx-7400G+ in the US) was already a bit outdated when I got my hands on it. It's first release was actually in the 20th century, and it absolutely felt like it. Most parents at the time bought newer, more capable models like the Casio’s Graph 35, or Texas Instruments’ TI-83, or even the TI-84 if they wanted to future-proof.

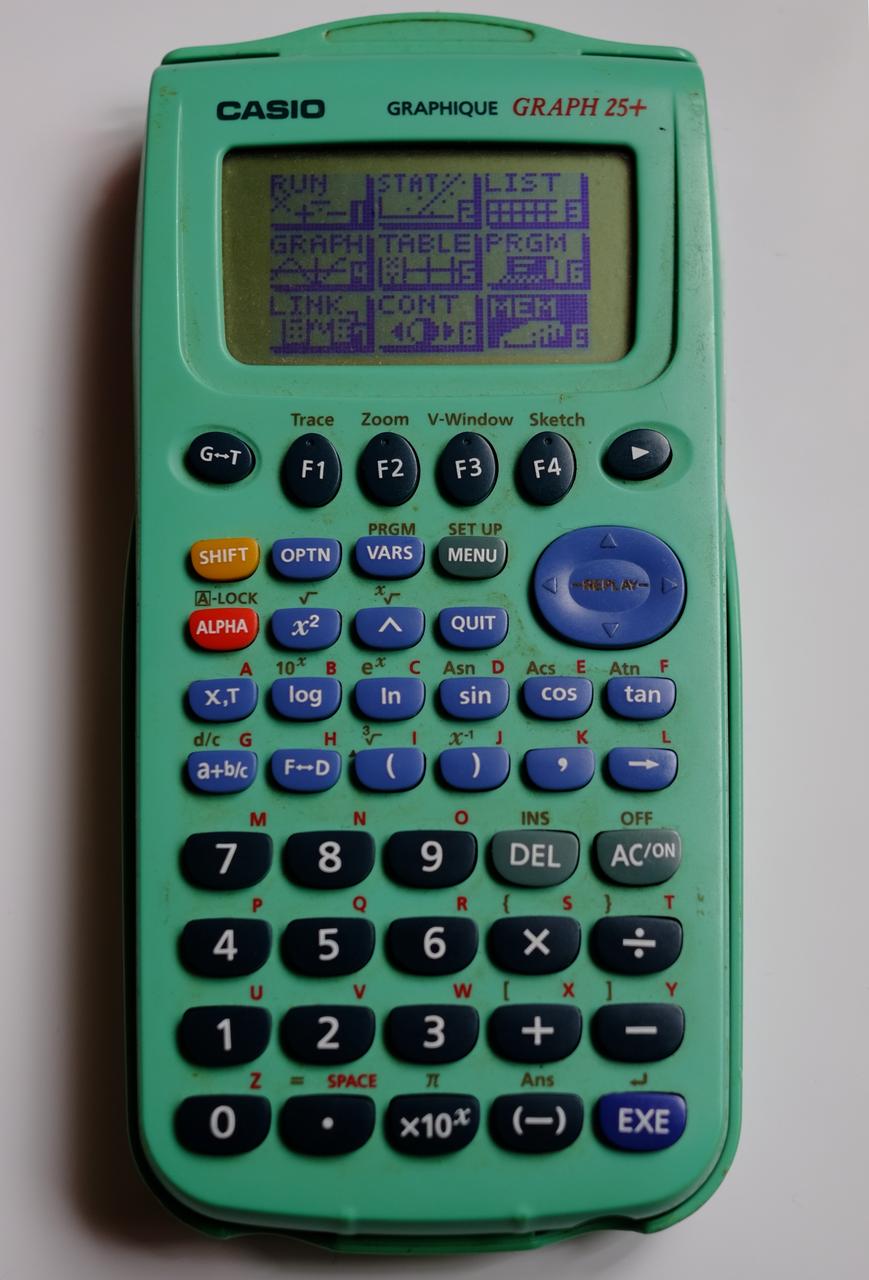

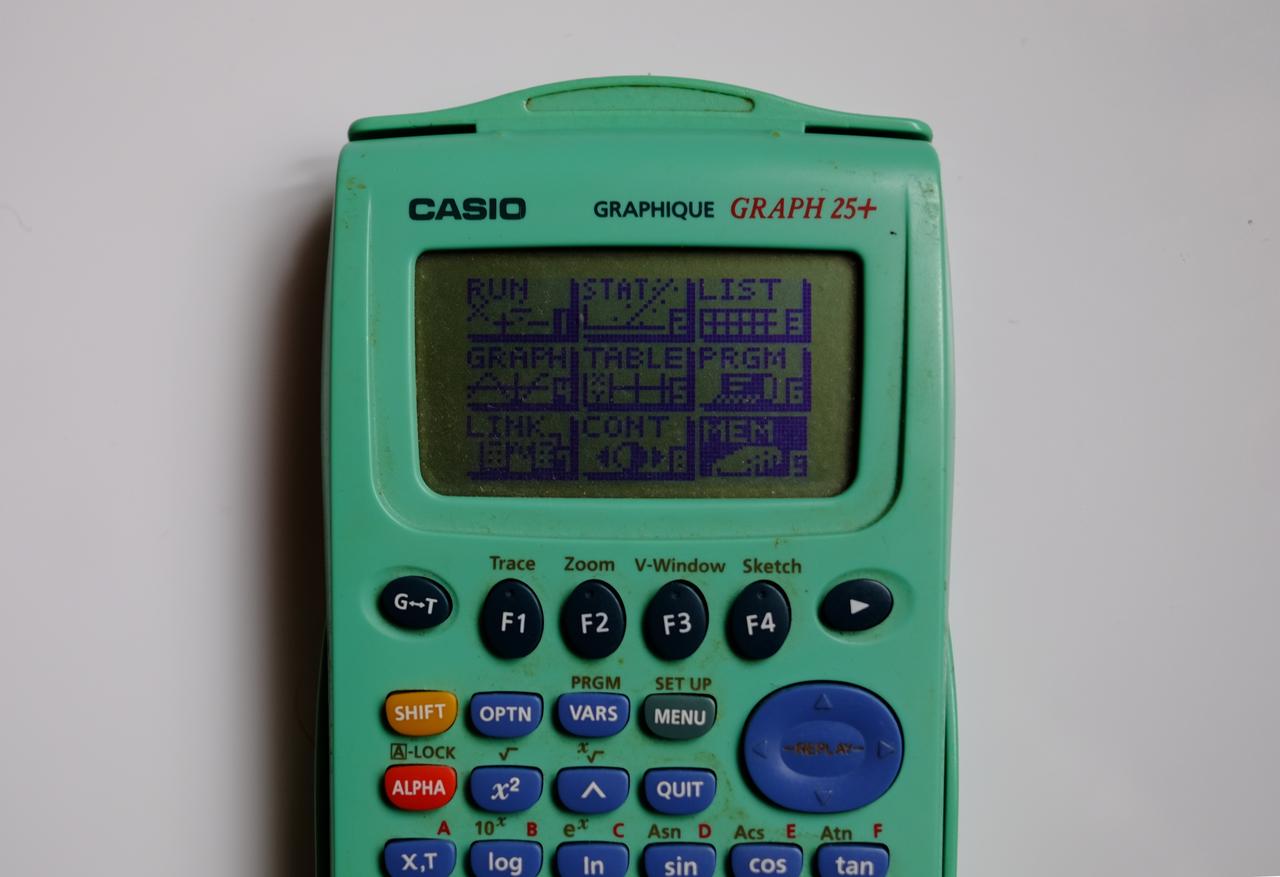

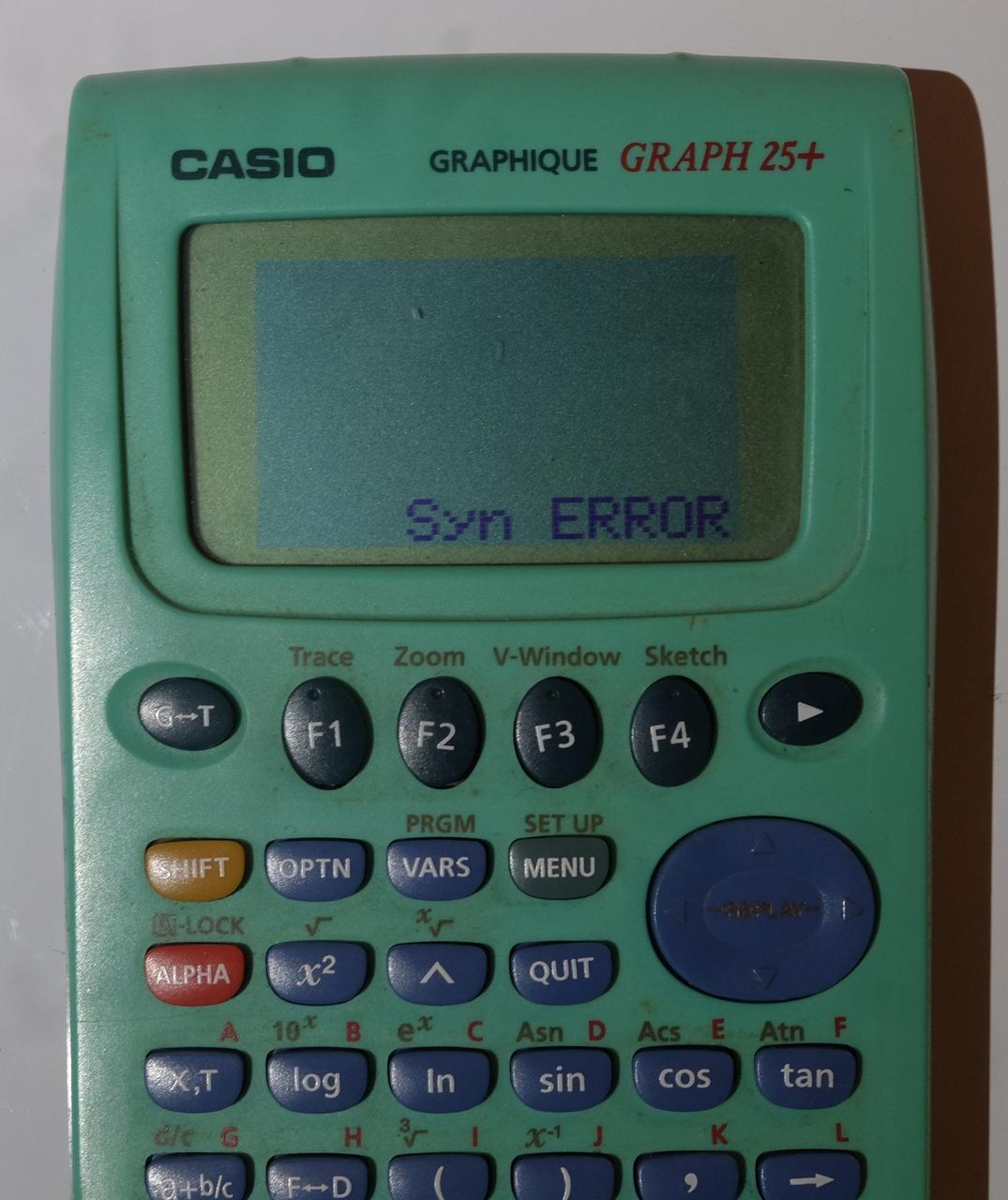

Mine, by comparison, isn't really sleek. The plastic is very thick and very green. The keyboard is fine, but the real bummer is the screen. We are talking about an 80×48 pixels monochrome, blue LCD dot matrix on a green-ish background with pretty atrocious contrast. It can make use of that amazing screen resolution to display exactly six lines of thirteen characters each. But don't get too excited, the first and last line are not available when programming, and so your program will be displayed 52 characters at a time. As for storage, you get some roomy 20 kB of non-volatile memory for programs and data combined. The OS is mercifully installed somewhere else.

The programming language is a distant cousin of the original BASIC, heavily modified for Casio calculators, and the code is interpreted at run time by an already very slow chip. An empty for loop from 0 to 1000 (and no output to the screen) will take around 4 whole seconds to execute.

You get exactly 26 numeric variables, and you do not get to choose their names. They’re simply called A through Z. Assigning a value to a variable looks like this: 10→A. You also get the equivalent of BASIC's INPUT command through the question mark command: ?→A.

Instructions can be separated either by : or by ↵. The latter represents an actual line break in the code listing. This distinction matters, because long lines are automatically wrapped by the editor, and not at word boundaries. Keywords will happily be split in half across lines, making the code even more painful to read.

Outputting to the screen is a bit weird too. You need to use the ◢ symbol after whatever you want to display ("HELLO"◢ will print HELLO, and A◢ will display the value of the variable A). It will print to the screen, and then halt the code execution, waiting for a keypress. For strings and numbers, you don't need the ◢. When by themselves, they are interpreted as display instruction by default and will perform a non blocking display. Unfortunately that does not work in loops.

Conditionals are pretty much standard BASIC, that is:

If <condition>↵ Then <instruction>↵ Else <instruction>↵ IfEnd

There is, however, a delightful quirk: if you omit IfEnd and there is no Else clause, then when the condition is false, execution jumps back to the start of the program.

Surprisingly you also get a ternary operator, which the documentation bizarrely classifies as a "jump command":

<condition> ⇒ <instruction_if_true> : <instruction_if_false>

Loops are standard BASIC, that is a While / WhileEnd, a Do / LpWhile and a For. But if structured programming isn’t your thing, Casio BASIC has you covered. You can label parts of your code using the Lbl command. There are unfortunately only 36 labels available: 0 to 9 and A to Z, but once labeled, you can jump there using Goto. Mercifully, Goto expects a label, preventing you from jumping to an arbitrary line number.

Finally, the language includes shortcuts like Dsz, Isz, commands to clear the screen, and functions to interact with the calculator plotting and tabular capabilities. There is also a way to interact with exernal sensors, but unfortunately for aspiring game developers, no addressing individual pixels. I believe the latter was added later on the 35+, but this one is a serious calculator, made for serious people, doing serious maths.

One word on code input. You don’t type keywords using the Alpha letters of the keyboard as you might have expected. Instead, you navigate menus that insert the entire word at once. Each keyword is a sequence of 4 to 5 keypresses. For exemple, getting an If statement is done this way:

- Shift → Vars (to open the PGRM menu)

- F1 (COM submenu)

- F1 again (the

Ifkeyword)

And finally, let's talk debugging. There is no help coming your way. At run time, you are given a few different error messages, like Ma Error for divisions by 0, and synError for syntax errors, but no line numbers and no hint of what is actually wrong. Better start printf() debugging!

3. Code Review of My Thirteen Years Old Self

Now that you’re up to speed, let’s take a look at what a thirteen-year-old kid actually coded.

Before you judge my past self, remember that this was my first real exposure to programming. At the time, I had no idea what a variable or a loop was. My internet access was almost nonexistent, so my sole source of information and the calculator’s user manual. And it is not a lesson or a tutorial, but a dry and technical documentation. I learned by carefully studying the few snippets and examples it contained, and by experimenting until something somewhat worked. Please be kind.

I’ve also copied the listings here using somewhat natural line breaks, and you get syntax highlighting for free. As a reminder, on the original calculator screen, the characters were monochomes and the display was limited to 4 lines of 13 characters each. I’ve also translated all the strings from their original French into English.

A Very Simple Start

One of the earliest and simplest programs I wrote looked like this:

"SALARY/YEAR"?→A↵ A÷12→A↵ A

If you’ve been following so far, this one should be easy to understand. It asks the user for a yearly salary, divides the number by twelve, and prints the corresponding monthly income. In retrospect, it’s a little depressing that the very first test program I ever wrote was about money...

Quadratic Equations

Next up is the following listing:

"AX²+BX+C"↵ "A:":?→A↵ "B:":?→B↵ "C:":?→C↵ B²-4xAxC→D↵ "DELTA =":D◢ If D<0:Then "NO SOLUTION":Goto 0:IfEnd↵ If D=0:Then -B÷2A→S:"SOLUTION =":S◢ Goto 0:IfEnd↵ If D>0:Then (-B-√D)÷2A→S:(-B+√D)÷2A→T↵ "SOLUTIONS =":S◢ T◢ Goto 0:IfEnd↵ Lbl 0

This is, unsurprisingly, a solver for second-degree polynomials:

$$\text{Given } ax^2 + bx + c = 0,\quad a \neq 0$$ $$\Delta = b^2 - 4ac$$ $$ x = \begin{cases} \dfrac{-b \pm \sqrt{\Delta}}{2a} & \text{if } \Delta > 0 \newline \dfrac{-b}{2a} & \text{if } \Delta = 0 \newline \text{no real solution} & \text{if } \Delta < 0 \end{cases} $$

It’s a solid implementation. If I really wanted to nitpick, I would point out the usage of labels and gotos to exit gracefully instead of using the Stop command, but other than that, I think it holds up pretty well.

Utility Programs and Not-Cheats

Beyond that, I found a handful of small programs solving very specific problems, along with several listings copied straight from the documentation. I also discovered a significant number of password-protected cheat sheets. Those programs were never meant to be run, but to store formulas and reminders. The password is obviously long forgotten, but you can easily imagine the contents.

And before you accuse me of cheating: this was (and to my knowledge still is) extremely common practice among students.

The Big Game

I want to end this chapter with the most ambitious program I wrote, the implementation of which I found interesting. Below is the original Casio BASIC code, as well as a faithful Python equivalent:

' The Original Casio BASIC 0→V↵ 0→W↵ "PLAYER 1, INPUT A NUMBER"↵ ?→X↵ ClrText↵ If X<0:Then Goto Z:IfEnd↵ If X>10000:Then Goto Z:IfEnd↵ Intg X→X↵ Lbl 1↵ "PLAYER 2, INPUT A NUMBER"↵ ?→Q↵ If Q>X:Then "IT'S LESS":IfEnd↵ If Q<X:Then "IT'S MORE":IfEnd↵ V+1→V↵ If Q=X:Then Goto 2:IfEnd↵ "PLAYER 3, INPUT A NUMBER"↵ ?→R↵ If R>X:Then "IT'S LESS":IfEnd↵ If R<X:Then "IT'S MORE":IfEnd↵ W+1→W↵ If R=X:Then Goto 2:IfEnd↵ Goto 1↵ Lbl 2↵ If V>W:Then "PLAYER 1 WINNER"◢ Else "PLAYER 2 WINNER"◢ IfEnd↵ "RESULTS"↵ "-------"↵ "J1→":V◢ "J2→":W◢ Goto 9↵ Lbl Z↵ "THIS IS NOT ALLOWED"↵ Lbl 9↵ Stop

# Almost line for line Python version v = 0 w = 0 print("Player 1, input a number") x = float(input()) os.system('clear') if x < 0 or x > 10000: not_allowed() x = int(x) while True: print("Player 2, input a number") q = float(input()) if q > x: print("It's less") if q < x: print("It's more") v += 1 if q == x: break print("Player 3, input a number") r = float(input()) if r > x: print("It's less") if r < x: print("It's more") w += 1 if r == x: break if v > w: print("Player 1 winner") else: print("Player 2 winner") print("Results") print("-------") print(f"J1->{v}") print(f"J2->{w}") def not_allowed(): print("This is not allowed") exit()

So what’s going on here?

This is a three-player game. Player 1 chooses a secret number between 1 and 9999, and Players 2 and 3 then take turns trying to guess it before the other does. It’s a very standard, but what I still like about it is how seriously I took input sanitization. The ? command will only allow real numbers, but on top of that I limited the range of allowed numbers and explicitly truncated the value to an integer. I must already have been burned by a few particularly cheeky classmates.

That said, the implementation is clumsy and contains an obvious mistake. The latter is easy to spot: I mixed up the player numbers in the result strings. Players 2 and 3 are the ones actually guessing, yet the program can declare Player 1 as the possible winner.

The implementation issue is more subtle. If Player 2 guesses the number correctly, the program immediately jumps out of the loop and declares a winner. Player 3 never gets a chance to guess during that round, making ties impossible, even if Player 3 would have guessed correctly on the same turn. This gives an inherent and unfair advantage to Player 2.

Ironically, it is this very unfairness that allows the program to determine a winner at all. The winner is inferred after exiting the loop by comparing the number of guesses each player made. If both players have the same number of attempts, Player 2 is declared the winner! A much cleaner approach would have been to explicitly track the winner using a dedicated variable defined outside the loop, and to set it before exiting. Conceptually, something like this:

winner = None i = 0 while not winner: print("Player 2, input a number") q = float(input()) if q > x: print("It's less") if q < x: print("It's more") print("Player 3, input a number") r = float(input()) if r > x: print("It's less") if r < x: print("It's more") if q == x: winner = "Player 2" if r == x: winner = "Player 3" if q == x and r == x: winner = "Tied" i += 1 print(f"Winner : {winner}\nNumber of guesses : {i}")

Obviously this would need to be adapted to Casio BASIC, or we could still optimize it a lot in Python, but the logic would have been much saner. And, finally, I just can't remember why we needed a Player 1 in the first place. A random number should have absolutely been enough.

Conclusion - Fifteen Years Later

In the end, I’m genuinely glad I had this experience. I was born too late to take part in the glory days computing in the 1970s and early 1980s. In a way, the humble Graph 25+ was my Commodore 64. The performance and the limitations, are surprisingly comparable, and it’s an experience I probably would never have had otherwise, and it really made me appreciate the niceties we have today.

Not long after, I was given an already old at the time Pentium III–based PC, running Windows Millennium Edition (!). My father, who was always very attentive to his children, noticed my growing interest and bought me a French translation of Stephen Davis' C++ For Dummies. I installed the recommended Code::Blocks IDE, wrote my first programs with a real keyboard, and never really went back to Casio BASIC.

And this is where the story ends - so far, at least. Let me thank you for trudging through this personal detour with me. I hope it brought back a few memories of your own, and maybe even made you look for the old calculator of yours, hidden somewhere in a drawer.

But what happened to the old girl, you might ask?

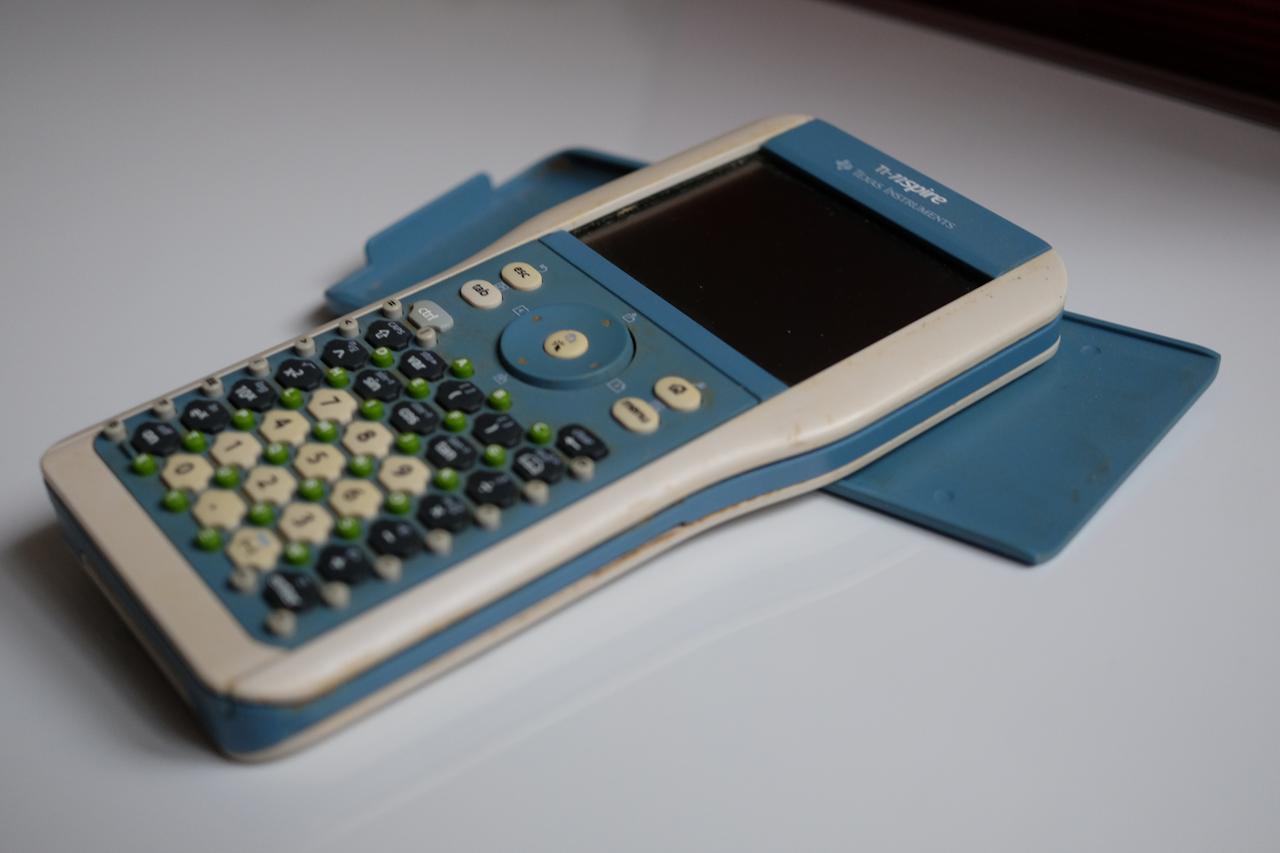

During my second year of high school, I managed to convince my parents that I needed a more powerful calculator (which was mostly true) and that it had to be a TI-Nspire (which was mostly false). I had heard that beyond the larger screen and faster processor, it had been jailbroken a few years earlier, and that an open source toolchain was written to compile C code that could run natively...

The Casio was retired and put into storage, where it remained until now. But rediscovering it and writing this article has given me a renewed appreciation for what it is and what it meant to me. I’ll power her up from time to time, and I'll make sure that the batteries don't leak. In the meantime, let me indulge my amateur photographer’s urge and give her the time in the spotlight she deserves.